|

| ED Galing with his lifetime Achievement Award ( photo from Philadelphia Inquirer--Luke Rafferty) |

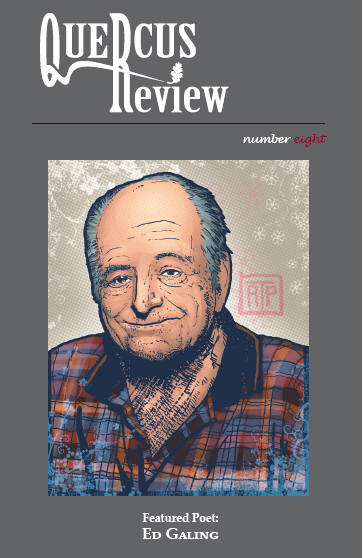

Ed Galing cannot get enough.

Enough attention. Enough praise. Enough love. Enough life.

And if he hasn't had his fill at 96, he is unlikely to ever feel completely sated.

"I love publicity," Galing said, with characteristic candor. "I'm famous!"

In June, the mayor of Hatboro gave Galing a lifetime achievement award for his more than 16 years as poet laureate of the Montgomery County town.

"It's like being in the Kennedy Center, and the president puts a medal around their neck," Galing said in his gravelly voice. "Lifetime achievement!" he marveled. "Not everybody gets that. You have to earn it."

Since his wife, Esther, died six years ago, he spends most days in his own still-plucky company. Alone, that is, except for an aide, who comes for a few hours a day, and his most loyal companion: a seafoam-green IBM Selectric typewriter.

Every morning at 5, he wakes up, gets out of the hospital bed in his first-floor office, transfers himself into his motorized wheelchair, and hums over to the desk to write for an hour or two.

"I write whatever comes into my head," he said. "Then I put it away and look at it the next day to see if I still like it. If I don't, I throw it away."

That rarely happens.

"I'm a good man, and I know how to write," he said. "Can I read you a poem?"

Without waiting for an answer, he pushes his thick thumb against the joystick of his wheelchair, so well-used that the black vinyl is as cracked and wrinkled as old skin. The chair catches on the threshold to the living room, and he coaxes it onward - "Go! Go!" - then bursts through into the living room.

The tchotchkes, vases, and family photographs remain exactly the way Esther left them, except for a new couch and armchair - gifts from one of their sons.

"He told me he's going to take care of me the best he can," said Galing. "He told me he loved me."

Galing reaches into a bookcase and pulls out one of the many collections of his work.

The World War II veteran graduated from South Philadelphia High School and worked in a variety of jobs, first at the Willow Grove Naval Air Station and, in his later years, processing sales documents for a car dealer. His last job, when he was 80, was custodial work at a restaurant.

That was the year he began writing in earnest, for personal expression, yes, but always, too, in the hope that his work would be recognized.

"Now, I'm in more than 400 publications," he said. "It's like George Bush's Mission Accomplished! Except this is real."

Real enough, in any case, to fill the deeply human need to feel significant. Especially at this far end of the trail. Hard of hearing and crippled by arthritis, Galing writes to be heard. To resist fading into his own shadow.

"If I was 60 right now," he reminisced in a recent letter, "I would be driving a car, going on vacation, making love with my wife, enjoying family picnics . . . and all of us would be young, and laughing, and so very happy."

Describing his life now, he continued: "My fingers are curled, and I live in my wheelchair all the time. However, I can still write."

Galing's poems have appeared in a few small literary magazines, like Red Wheelbarrow and Rattle, and he is a regular contributor to a newspaper for the homeless in Nashville. Much of his work is self-published, such as Pushcarts and Peddlers, a collection of pieces about his childhood in the early 1900s among other poor Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side of New York.

"It didn't sell as much as I had hoped," he said. "People don't read much anymore."

For a moment, his brave front faltered.

"I'm not really famous," he said. Then he rallied. "But I'm very well-known and very well-liked in the field."

He came too late to computers to master the new technology, he said, but Doug Holder, a fellow poet in Massachusetts, helps him blog by proxy, and praises him as "a poet of the Greatest Generation."

Galing found the poem he was looking for in the bookcase. It describes his childhood in New York, the rooming house where he lived with his mother, and his habit of sitting outside during the hot summers, writing poems on sheets of paper that he would fold into paper airplanes, launch, and watch flutter to the sidewalk.

where the garbage collectors

would sweep it

away

with the rest

of the garbage.

Galing, proud, smiled with satisfaction, plumping up his doughy cheeks.

"Sometimes, I wonder what am I doing, living here in this house with only health aides. It's lonely," he said. "But I don't want to die. I'm going to keep writing till the end of my life."